Object-Oriented Programming (OOP) is a paradigm that organizes software design around data, or objects, rather than functions and logic. Objects can be defined as instances of classes, which can be thought of as blueprints for creating objects. OOP focuses on utilizing these objects to design and build applications, allowing for more modular, reusable, and maintainable code.

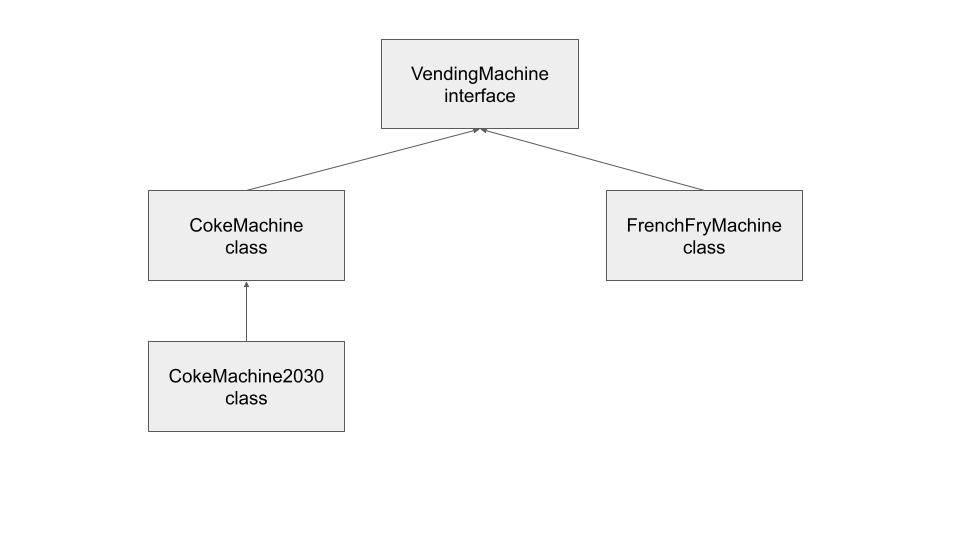

private, protected, and public. Encapsulation helps in protecting an object's internal state and ensures that it can only be changed in controlled ways.Car class can inherit from a Vehicle class, gaining all the attributes and methods of a vehicle.Shape class might have a method draw(), and subclasses like Circle and Square can provide their own implementations of draw().To illustrate these concepts, let's model a vending machine system. We'll create a base class for vending machines and derive specific types of machines, like a Coke machine, a futuristic Coke machine, and a French fry machine.

The VendingMachine class serves as an abstract base class, providing a common interface for all vending machines. It uses a pure virtual function to enforce implementation in derived classes.

class VendingMachine {

public:

virtual void dispenseItem() = 0; // Pure virtual function

virtual ~VendingMachine() {}

};

This class defines the interface for vending machines, ensuring that any derived class must implement the dispenseItem() method.

The CokeMachine class inherits from VendingMachine and provides its own implementation of the dispenseItem() method.

#include <iostream>

#include "VendingMachine.h"

class CokeMachine : public VendingMachine {

public:

int numberOfCans;

CokeMachine() {

numberOfCans = 2;

std::cout << "Adding another coke machine to your empire" << std::endl;

}

void dispenseItem() override {

if (numberOfCans > 0) {

numberOfCans -= 1;

std::cout << "Have a Coke" << std::endl;

std::cout << numberOfCans << " cans remaining" << std::endl;

} else {

std::cout << "Sold Out" << std::endl;

}

}

};

int main() {

CokeMachine machine;

machine.dispenseItem();

machine.dispenseItem();

machine.dispenseItem();

return 0;

}

Here, CokeMachine encapsulates the behavior specific to dispensing Coke.

The FrenchFryMachine class also inherits from VendingMachine and implements its own version of dispenseItem().

#include <iostream>

#include "VendingMachine.h"

class FrenchFryMachine : public VendingMachine{

public:

int numberOfFries;

FrenchFryMachine() {

numberOfFries = 2;

std::cout << "Adding another french fry machine to your empire" << std::endl;

}

void dispenseItem() override {

if (numberOfFries > 0) {

numberOfFries -= 1;

std::cout << "Have some french fries" << std::endl;

std::cout << numberOfFries << " fries remaining" << std::endl;

} else {

std::cout << "Sold Out" << std::endl;

}

}

};

int main() {

FrenchFryMachine machine;

machine.dispenseItem();

machine.dispenseItem();

machine.dispenseItem();

return 0;

}

This class demonstrates polymorphism, as it provides a unique implementation of the dispenseItem() method.

The CokeMachine2030 class extends CokeMachine with additional features, showcasing inheritance and polymorphism.

#include <iostream>

#include "VendingMachine.h"

class CokeMachine2030 : public CokeMachine {

public:

void dispenseItem() override {

if (numberOfCans > 0) {

numberOfCans -= 1;

std::cout << "Dispensing a futuristic Coke with AR experience..." << std::endl;

playARExperience();

std::cout << numberOfCans << " cans remaining" << std::endl;

} else {

std::cout << "Sold Out" << std::endl;

}

}

void playARExperience() {

std::cout << "Playing Augmented Reality experience..." << std::endl;

}

};

int main() {

CokeMachine2030 machine;

machine.dispenseItem();

machine.dispenseItem();

machine.dispenseItem();

return 0;

}

This class overrides the dispenseItem() method to provide a more advanced experience and adds a new method playARExperience().

We can utilize polymorphism to treat all these machines as VendingMachine objects, calling their dispenseItem() methods uniformly.

void operateVendingMachine(VendingMachine* machine) {

machine->dispenseItem();

}

int main() {

CokeMachine cokeMachine;

FrenchFryMachine fryMachine;

CokeMachine2030 cokeMachine2030;

operateVendingMachine(&cokeMachine); // Outputs: Dispensing a Coke...

operateVendingMachine(&fryMachine); // Outputs: Dispensing French Fries...

operateVendingMachine(&cokeMachine2030); // Outputs: Dispensing a futuristic Coke with AR experience...

return 0;

}

Because an object of a class that implements an interface is also an object of that interface type. That concept is the basis of an important object-oriented programming principle called polymorphism.

Polymorphism is derived from the word fragment poly and the word morpho in Greek, and it literally means "multiple forms".

Polymorphism simplifies the processing of various objects in the same class hierarchy by using the same method call for any object in the hierarchy. We make the method call using an object reference of the interface.

(From the movie "Happy Feet")

Let's say that you've been inspired by the previous discussions and decide to create commercial vending-machine simulation software. To make this work, you'll need to accommodate vending machines beyond those that sell only Coca-Cola products. For example, you may want to include...

Because the alternative to polymorphism is to write lots of chunks of code that look like sort of like this (if they were written in English):

if we want to vend an item from foo1 and foo1 is a CokeMachine2030

then print "have a futuristic Coke" else

if we want to vend an item from foo1 and foo1 is a FrenchFryMachine2025

then print "have some french fries" else

if we want to vend an item from foo1 and foo1 is a CokeMachine2025

then print "have a Coke" else

if we want to vend an item from foo1 and foo1 is a PizzaMachine2025

then print "have a previously frozen pizza" else ...

As the number of classes within the same hierarchy grows, so does the size of the chunks of code represented above. Ew!

Why do we care about organization? Because when programs get real (where real == big), a well-organized program will make your programming life easier.

As part of a simulation of the behavior of gas stations, you are to create a class definition called GasStation. Each object of the GasStation class keeps track of how many gallons of gasoline are available at that gas station, represented as an integer. A GasStation object also has a method to simulate the dispensing of some number of gallons of gasoline. That method, called dispenseGas(), reduces the amount of gasoline available at that gas station by the number of gallons dispensed, assuming there are at least as many gallons available as the number of gallons to be dispensed. If the number of gallons of gasoline to be dispensed is greater than the number of gallons available, then no gasoline is dispensed. Another method, called getAvailableGas(), returns the number of gallons of gasoline available at that gas station. Every gas station object has 10,000 gallons of gasoline when it is created. The dispenseGas() method always dispenses exactly 100 gallons of gasoline when it is invoked.

Here's a simple program that we might use to test your GasStation class:

#include <iostream>

int main() {

GasStation chevron;

GasStation shell;

std::cout << "Chevron has " << chevron.getAvailableGas() << " gallons." << std::endl;

chevron.dispenseGas(); // 100 gallons dispensed

chevron.dispenseGas(); // 100 more gallons dispensed

std::cout << "Chevron has " << chevron.getAvailableGas() << " gallons." << std::endl;

std::cout << "Shell has " << shell.getAvailableGas() << " gallons." << std::endl;

shell.dispenseGas(); // 100 gallons dispensed

std::cout << "Shell has " << shell.getAvailableGas() << " gallons." << std::endl;

return 0;

}

FooCorporation. Write a method calculatePay to calculate and display the pay for an employee based on the following criteria:

calculatePay method should take 3 arguments:

<EmployeeName> has a total pay of $<TotalPay>.

CokeMachine class to include a method for adding coke to the machine.VendingMachine pointers and calls dispenseItem() on each.